So You Want a Scottish Gaelic Tattoo – Part One

So you want to get a tattoo — in Scottish Gaelic. You want to honour a family member, or your Scottish heritage, or you just think the Gaelic language is cool, but you don’t speak Gaelic yourself. What should you do?

If you’ve already designed your tattoo, and you know exactly what you want it to say, your first impulse will probably be to turn to the internet for a translation. Here in Part One I’ll show you why that’s not a good idea, and in Part Two, I’ll give you some advice if you still really have your heart set on a Gaelic tattoo.

Now, how do you think you’re going to get a translation on the internet? Online translating services don’t do Scottish Gaelic (yet). This is what happens when you’re dealing with a “lesser-used” language. There just aren’t that many of us Gaelic speakers around, and so large companies tend not to cater to us with goods and services. But even when online translating services do offer Scottish Gaelic, beware. Google Translate made a hash of Irish, and online translators generally don’t work that well.

So maybe you find an online dictionary and try to do the translation yourself. You will still end up with a Bad Gaelic Tattoo. For example:

“FREE DRUGS – AND I CAN’T SPELL” – a bad Gaelic tattoo translation

Although this particular tattoo was intended to be in Irish, I’ll discuss it here because bad Scottish Gaelic tattoos have the exact same problems.

The bearer of the tattoo believes that it says “DRUG FREE.” The idea of a person declaring her/himself “drug free” is a specific American English cultural concept. It’s a declaration that the person in question does not take alcohol, nicotine, or recreational drugs that are illegal in the U.S. This orientation to drugs is a cultural phenomenon or movement known as “Straight Edge.”

Apart from the problem that the cultural concept does not translate, this tattoo has fatal spelling and grammar problems. In Scottish Gaelic, “drug” is druga or droga and the plural, “drugs,” is drugaichean. In Irish it’s singular druga and plural drugaí. Gaelic words don’t have apostrophes in the middle, and “-ail” is not a plural suffix. So “drug’ail” is not a Gaelic word.

When confronted with this information by blog commenters, the tattoo bearer insisted that her trusted friends who were raised Irish-speaking in Ireland had given her this translation. She said: “Fine; whatever. The people that I know say that I’m right; the Irish Gaelic-English dictionary says that I’m right. But, go ahead guys. Tell me that my tattoo is wrong. It doesn’t matter. I’m happy with it.” She stated that she had also looked up “drug” in an English-Irish dictionary and found the word drugáil, and that the apostrophe was supposed to represent the fada (or srac in Scottish Gaelic) over the á.

Another commenter pointed out that in the dictionary where the tattoo bearer looked it up, drugáil was defined as a transitive verb, in the sense of “to drug (someone).” More precisely, it is a verbal noun which means “drugging.” Additionally, apostrophes are not used as substitutes for accent marks in Irish or Gaelic (or in French or Spanish for that matter).

Beyond that, the adjective saor does mean free, but it’s not used in the same way as “free” in English. If you wanted the sense of “free” that’s in the English expression “drug-free,” the sense of being not under the control of drugs, or of drugs being absent from one’s life or body, then it might make sense to use the expression gun (“without”). Except that gun also changes the first sound of the following word, if it’s a consonant, so that would make it literally “gun dhrugaichean,” without drugs, except that in this case the n blocks lenition of homorganic t and d, so it’s “gun drugaichean,”… but even that does not have the Straight Edge connotation of the English phrase “drug free.”

So the way this tattoo reads to a Gaelic speaker is either “FREE DRUGGING” or “FREE DRUGS” with a side helping of “I CAN’T DO IRISH SPELLING OR GRAMMAR.”

After multiple Irish speakers left comments pointing out that her tattoo was incorrect, the tattoo bearer finally stated: “It’s already on my back, right or wrong, and the sentiment is still there. I did research for two years before I got the tattoo, and no one ever told me it was wrong until after I got it. So, fine. It still means the same thing to me that it always did.”

The end result is that an English-speaking woman paid a large sum of money to have broken bits of Irish inscribed across her back for others to see, but it only means something in her own mind. To the fluent Irish speakers of the world, it’s garbled nonsense.

This ex-U.S. paratrooper got a Scottish Gaelic tattoo to commemorate his multi-generational family tradition of airborne military service:

“Report to the People” instead of “Family Tradition” – A bad Gaelic tattoo translation

The tattoo was supposed to read “FAMILY TRADITION” but it’s a train wreck. This is what happens when you try to look up English words in a Gaelic dictionary and then string them together according to English grammar rules.

Beul-aithris means “oral tradition” and so perhaps this person thought that aithris just meant “tradition”, but aithris means “report,” “account,” “recitation,” or “narration.” For example, Aithris na Maidne (Morning Report) is the name of the BBC’s Gaelic morning radio news program.

Dream can mean “people,” “kindred,” or “folk,” but it’s not the usual Scottish Gaelic word for family (which is teaghlach). “Á” means “out of” and so it’s possible that they mistook this for “of” (which is de), while also omitting the srac over the “á.” Apart from the word being wrong, however, this grammatical construction (family tradition, that is, tradition of the family) would actually require the genitive case in Gaelic. The genitive case is a category that nouns fall into when they are used in expressions of possession, measure, or origin. In English we can use either a possessive form or “of” to indicate this relationship, for example: “Mary’s coat” or “the coat of Mary”; “a month’s vacation,” or “a month of vacation.” In Gaelic, nouns are modified in spelling and pronunciation when they are used in the genitive case. In the literal Gaelic translation of an English phrase like “family tradition,” in other words “tradition of the family,” the word for family (teaghlach) would be written in the genitive case (in this case teaghlaich).

Even “dualchas teaghlaich” sounds a bit odd however, because it’s redundant. Ironically, the word dualchas alone would have sufficed to convey the meaning he wanted.

So the way this tattoo reads to a Gaelic speaker is: “REPORT OUT OF THE PEOPLE (AND I DON’T KNOW GAELIC)”

Even when you think you know what your tattoo says, are you sure that the spelling and grammar are correct? This one was supposed to say “ALBA SAOR” — “FREE SCOTLAND” (where “free” is an adjective, not an imperative verb). Instead a spelling mistake transforms “saor” into “soar” — an easy mistake to make when neither you nor the tattoo artist knows Gaelic, and the English word “soar” is so close in spelling.

“Soar Alba” instead of “Alba Shaor” (free Scotland) – a bad Gaelic tattoo translation

The placement and spelling of the adjective “saor” (free) are also problems. Again, Gaelic is not like English. In regard to adjective placement, it’s more like French: most of the adjectives go after the noun, and a small number are placed before the noun. And like French, adjectives change when they modify feminine nouns. Saor goes after the noun, and it modifies Alba which is feminine, so it should be “Alba shaor.”

If “saor” is placed before the noun, it’s an imperative verb, an order to “Free!” or “Liberate!” as in, “Free Nelson Mandela.” But the imperative in Gaelic comes in two versions, singular and plural, and this is the singular — an order given to one person only, and someone familiar or lower in status at that.

So it’s a lovely sentiment, but to a Gaelic speaker this tattoo looks like it says something like “DUDE, LIBARETE SCOTLAND! (AND I DON’T KNOW GAELIC)”

How about this one? Celtic knotwork + Gaelic = seems legit.

A misspelled Gaelic tattoo translation

But it’s not, because grammar. Gaelic is a Celtic language and one unique feature of the Celtic languages is something called initial consonant mutation. In Scottish Gaelic, depending on certain grammatical features of a sentence, the way that you pronounce the first consonant of a noun will often change. In this case, the possessive “mo” (“my”) lenites the initial consonant of the noun it modifies. In the Scottish Gaelic writing system this is indicated by placing an “h” after the initial consonant. Mo + seanair = Mo sheanair. Mo + gràdh = Mo ghràdh. This changes the pronunciation of the word differently according to which sound is being lenited. (If the noun starts with a vowel, then it’s just m’ instead of mo. Mo + anam = M’anam.) A dictionary will not tell you these things.

Also, this tattoo text sounds a little weird, like the person’s grandfather is their lover.

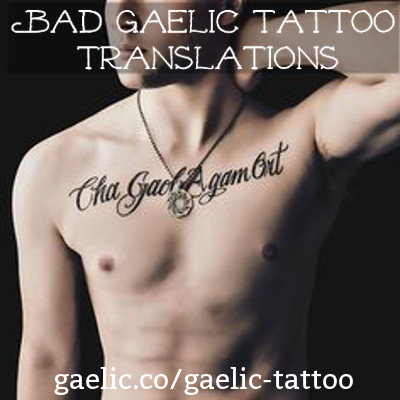

What about this one? You can’t go wrong with “I Love You”, can you? Any reasonably diligent internet search can tell you that “I love you” = “Tha gaol agam ort” (literally ‘love is at me on you) in Gaelic. But:

“I Not Love You” – a bad Gaelic tattoo translation

The artist accidentally used a capital “C” instead of a “T” — not a Gaelic mistake per se, just a common mistake in calligraphic font usage. But the result is hilariously bad Gaelic: the first word looks like “Cha” instead of “Tha”. “Cha” isn’t grammatical here, but it instantly puts Gaelic speakers in mind of “Chan eil“, as in “Chan eil gaol agam ort,” as in “I do not love you.”

So the way this tattoo reads to a Gaelic speaker is: “I Not Love You.”

Thank goodness it’s probably just Photoshopped, like the model’s abs.

Anyway, you get the picture. You might not want to rely on looking up individual words in a dictionary and stringing them together, and there’s no guarantee that your friends are correct, either. There’s no guarantee that the Gaelic phrases you find in books, or on Pinterest, or even for sale on jewelry, are correct either. The same goes for Irish, as this helpful article points out.

So you turn to the other thing that the internet is good for: connecting with total strangers. You look for a discussion group on social media. Maybe you find a discussion board devoted to Scottish culture, or a Facebook group devoted to the Gaelic language. You post a query. Here are some typical Gaelic tattoo requests on social media:

“What’s ‘three beautiful girls’ in Gaelic?”

Gaelic tattoo request

“What’s ‘I am my beloved, my beloved is mine’ in Gaelic?”

Gaelic tattoo request

“What’s ‘king’ and ‘queen’ in Gaelic?”

Gaelic tattoo request

“What’s ‘I am not finished’ in Gaelic? What’s ‘start somewhere’ in Gaelic?”

Gaelic tattoo request

“What are these 3 different phrases in Gaelic before my friend’s tattoo appointment tomorrow?”

Gaelic tattoo request

“What’s ‘Father until we meet again may God hold you in the hollow of his hand’ in Gaelic?”

Gaelic tattoo request

“What’s ‘Home is behind, the world is ahead’ in Gaelic?”

Gaelic tattoo request

This kind of tattoo translation request gets several kinds of reactions in online forums:

1) Well-meaning attempts to give you the translation you want, from people who are not qualified. There are a lot of adults learning Gaelic who are not yet fluent in the language or knowledgeable about the culture. With their help, if you are lucky, you may end up with a translation that is literally correct, but sounds awkward and weird. This may be because that thing you want your tattoo to say is not ever actually said in Gaelic. Just because something can be translated does not mean that the results will actually make cultural sense, or carry the poetic connotations that you want your tattoo to express. And if you are unlucky (or if you try to use a dictionary yourself), as you can see above, all bets are off as far as vocabulary, spelling, and grammar.

2) Genuine translations from people who are fluent in Gaelic. You’ve asked for help, and they feel obligated to give it, even though they may also advise you that the accurate translation they gave you doesn’t sound quite right in Gaelic. If you’re lucky, they might make an alternate suggestion which would be more suitable.

3) Frustration, sarcasm, or anger at yet. Another. Tattoo. Request. Fortunately for you, most fluent Gaelic-English bilingual people are actually pretty nice about tattoo requests, even when they are frustrated. Probably 99% of them won’t lead you astray by giving you fake translations that are actually declarations about the size of your genitals… but some may fantasize about doing so. Are you willing to take that risk? Especially if you plan to share photos of your tattoo online?

Here’s the thing: you will have no way of knowing whether you’ve been given a decent translation or not. That’s a major risk to the integrity of your body art.

Next, consider the ethics of these requests. First, you want something for nothing. Second, to be honest, you are wasting people’s time and effort on something that doesn’t really help Gaelic. Can you imagine if you were at work, doing whatever job you do, and people kept emailing you or popping up in your social media feeds once or twice a day, every day, to ask you to help them with the wording of their tattoo? That’s basically what happens to a lot of people who work in Gaelic language jobs. People are asking them for Gaelic translations of symbolic English phrases, for free, all. The. Time. How do you say “Happy Birthday” in Gaelic? How do you say “Merry Christmas” in Gaelic? How do you say “You shall not pass!” in Gaelic? How do you say “F off and die” in Gaelic?

What’s the big deal, though? You only want a tattoo. It will only take a total stranger, like, a few minutes to translate “One Ring to Rule Them All” into Gaelic for you. And Gaelic is SO COOL.

But Gaelic is not like English. It’s a minority language and culture that multiple governments have tried for many hundreds of years to stamp out. Its speakers have been pressured and even forced to abandon it and assimilate to English. Many were beaten in school for speaking Gaelic. It’s amazing that Gaelic speakers are still keeping the language and culture going. Gaelic is also what we call an “endangered” language, because efforts to stamp it out have been so successful in the long run that the number of speakers is still decreasing, and the language is in great danger of disappearing altogether. The “cool” factor comes in part from its rarity and double-edged romantic stereotypes of being ancient, natural, and poetic (= obsolete, animalistic, and good for nothing but poetry).

Endless free tattoo translation requests from English speakers are like death by a thousand papercuts. They suck up the energy and goodwill of an endangered language community and give nothing back.

A proliferation of bad Gaelic tattoos also weakens the language. How? Every bad bit of Gaelic that is put out there becomes an exemplar that other people may follow. It propagates mistakes (Soar Alba!), spreads ignorance, and makes the language more and more like a bad copy of English, and less and less like Gaelic. Change happens to every language whether people like it or not, but when the direction of change is taking it into convergence with a juggernaut like English, that’s called language death.

This is the reality of an endangered language.

Having said all this, if you still have your heart absolutely set on getting a Gaelic tattoo, I will have some concrete suggestions for you in my next blog post.

UPDATE: Fifteen hours after posting, I’ve already received a Gaelic tattoo translation request via e-mail! I don’t do Gaelic tattoo translation requests; to understand why, please read this post again. Please do not post tattoo translation requests in the comments or through e-mail. Also, please read Part Two of this post! Tapadh leibh.

Hi,

My wife is about to have our first child and i was interested in getting a nice auld scots saying for my baby boy.

Is there anything that you could suggest??

thanks

Thanks for your comment! As explained in the last paragraph of the post above, I can’t do Scottish Gaelic tattoo translations. There is also a second post that explains what to do if you have your heart set on a Gaelic tattoo despite the pitfalls.

However, from your question it sounds like maybe you are interested in getting a tattoo in the *Scots* language and not the *Scottish Gaelic* language? They are two separate languages: Scots is more closely related to English, German, and Dutch, while Scottish Gaelic in contrast is a Celtic language related to Irish, Manx, Welsh, and Breton. I explain the differences a bit more in this blog post: http://emilymcfujita.com/what-is-gaelic/

I’m not a speaker of Scots myself (although I can understand a lot of it!). So if it’s Scots you’re after, the language of Rabbie Burns’s poetry, then you could try posting your request in the public Facebook group Scots Language Forum:

https://www.facebook.com/groups/126242628908/

You could also read the poetry of Robert (Rabbie) Burns which is available free online here:

http://www.robertburns.org/works/

It is possible to search the poetry, so perhaps if you search on the Scots word “lad” or “laddie” you might find something suitable. (But if it contains words you dinnae ken, then best to confirm it with the Scots Facebook group above!)

If interested in Gaelic he could always read or watch The Outlander series of books by Diana Gabaldon in addition to the book on this page. She does well by the language from what I can tell. Although there are some words I dinnae ken ? I truly enjoyed your blog as well. ‘‘Tis Bonnie

Thank you very much for the compliment! Unfortunately the Gaelic in the Outlander books is pretty bad, although it improved with each subsequent book, as the author started to get more help with the language. I do not recommend learning Gaelic from the books, although they are a wonderful way to increase awareness of the language! I’ve written a blog post about how non-Gaelic-speaking authors use Gaelic in books that might interest Outlander fans: https://gaelic.co/gaelic-for-authors/

Hi, also looking for a tattoo translation of “I will take their pain”

Or “death awaits anyone who hurts daddy’s girls”

Any kind of sentiment that follows those notions would be great.

I am of distant Scottish decent and my daughters are 2nd generation Scottish/Irish

Great post, thanks for it. Very clearly illustrates how problematic these tattoos and requests can be. Tha mi beagan gaidhlig, I just started taking classes (on top of DuoLingo). Wondering how you would say “If you actually read the article I wrote, you wouldn’t be asking for tattoo translations.” Haha, thanks again. 😉

‘Se ur beatha! Agus mòran taing airson a leughadh! I definitely “buried the lede” as they say in journalism. 😉

Tha sin sgoinneil, cum oirbh le Duolingo!

I am trying to find i love you back

Why does your link take me to an Asian porn site?

Firstly, I’m very glad that you found your way here to my real website. The explanation is that it’s something horrible that was done by someone else to the original domain name I used for this site, after I let the registration lapse. The original domain name was based on a nickname that my students had for me. However, I stopped paying for that domain name registration about 8 years ago after I switched to “gaelic.co.” I thought it would be wise to save money, and I thought there was nobody else in the world who would find that domain name useful. But unfortunately, some time after that, it looks like the old domain was taken over and set up as a hardcore porn site. 🙁 I’m very upset about it, but there’s nothing I can do about it now. Had I realized it was a risk, I definitely would have continued paying every year for that domain name for the rest of my life, just to prevent it from happening! If you can let me know exactly where you found the link that is still pointing to the old URL, if it’s on my site I will change it to the current site URL instead. And if it’s on someone else’s site, you can ask them to change it to “Gaelic.co” or refer them to me and I will ask them.

Hi Fran, I was hoping you would acknowledge my comment and let me know where you found the outdated link!

I’m interested in learning true Gaelic here in Oklahoma. I am of scottish descent through the McMullen and have a great appreciation for the culture. Where should I start?

Hi Ross, thank you very much for your comment. It’s great to hear that you are interested in learning Scottish Gaelic! I’ve written an article about how to start learning Gaelic, which you might find helpful. There’s a PDF posted here:

https://www.academia.edu/11228443/_Learning_Scottish_Gaelic_in_Celtic_Life_International_Magazine

Google United Scottish Clans of Oklahoma. We currently (2016) are offering Gaelic classes in the metro area.

Slainte mhath!

Kris, thank you so much for posting this info here! Mealaibh ur naidheachd on offering Gaelic classes in Oklahoma, that’s a great achievement!

i would like to ask you if i can get you or someone to transluate an irish saying into ancient gaelic script for a tatoo

James, thank you for your comment. Before I can answer your question, I would need to ask you to clarify your request:

1) This blog focuses mainly on Scottish Gaelic, and not on Irish. For a bit of insight on how those languages are different, see my blog post https://gaelic.co/what-is-gaelic, or Chapter 2 of The Scottish Gaelic Tattoo Handbook.

2) Is your “irish saying” in English, or is it in modern Irish Gaelic (Gaeilge), or in Old Irish?

3) If it’s in English, then are you willing pay someone to have it (a) translated into Irish Gaelic and then (b) transliterated or retyped in a different font?

4) Which “ancient gaelic script” are you asking about – (a) ogham, (b) a medieval manuscript font such as used in the Book of Kells; or (c) a ‘clò gaedhlach’ font such as used for print books in Ireland a century ago, based on the medieval manuscript fonts? Do you have a sample image of what you have in mind? I give examples of different Celtic fonts in my book The Scottish Gaelic Tattoo Handbook.

I would love toe English /Scottish translation for “for my daughers I would risk it all”

Or similar…

Looking for a tattoo for my 2 girls to feel honoured by.

My mother, Virginia Lee Morris(on) b. 11/17/1920 Tulsa OK was a direct descendant of the Morrison clan/William P./brother of Andrew Carnegie’s mother Margaret/father and namesake of my grandfather Leander Milton ‘Lee’ Morris b. 10/5/1891 Oakmont PA.

My mother was a proud member of First Families of the Twin Territories. Just wanted to share both my Scottish and my ‘Okie’ roots with you. My father was born in OKC 4/30/1920 and attended Northeast High and O.M.A.. My oldest brother was born in Tulsa 11/30/44 thanks to Daddy being overseas war time, being a career U.S. Marine/Pearl Harbor Survivor.

Not sure if this is still a thing, but im very interested in learning scottish Gaelic. Im of scottish decent also from the Macphail clan. Also may be a long shot.. and of topic.. but i dont suppose if you know where to begin if i wanted to learn Norse also

Jayden, thanks for reading! Yes, learning Scottish Gaelic is definitely a Thing. Check out my blog post “Learning Scottish Gaelic” for advice on how to start: https://gaelic.co/learning-scottish-gaelic/

No idea about Norse, sorry! (Although there was also a good deal of Norse influence on Scottish Gaelic, so you may enjoy learning about that as you move ahead with learning Gaelic!)

hi i want to find out how to find the the scottish name for wendy

By “scottish name” I assume you mean the Scottish Gaelic name? Unfortunately I can’t do tattoo translations here (as explained above in the blog post). Your question is actually an interesting one and quite complicated to answer. I’ll make it the subject of a blog post later this month or next, so if you subscribe to the blog you can find out the answer to your question.

I’ve just published a new blog post that answers your question — “The Gaelic for Wendy”! Check it out at: https://gaelic.co/gaelic-wendy/

Do you have a recommendation of where to look to find a legitimate translator? I would happily pay for a correct translation and to support the efforts to keep the language alive. I have Scottish heritage through Clan Robertson and have always felt drawn to the history and spirituality of the country. I can’t wait to visit the highlands one day. I currently live in the USA.

Yes, look up Alasdair MacCaluim at “gaelicalasdair” on fiverr.com, or Michael Bauer at akerbeltz.com. Either one of them will do a great job for you! Take a look at Mango languages app right now if you want to get started learning a taste of Gaelic for your future trip — I hope you get there soon!

Hello – please would you tell me what this means in English; alba an algh

I bought a bracelet for one of my children and it inscribed with that upon it. I would like to know what it means before I give it to them!

Many thanks and kind regards

Trisha

Wikipedia gives “Alba an Àigh” as the poetic Gaelic “translation” for “Scotland the Brave,” but it doesn’t mean Scotland the Brave in Gaelic. “Àgh” means something like happiness or prosperity. In this phrase, the noun àgh is in the genitive case so it’s spelled “àigh.” The translation would be something like “Scotland of Happiness” or “Scotland of Prosperity.” I’ve never seen it used in Gaelic, however!

The phrase “an àigh” is most commonly used in the Gaelic Christmas carol “Leanabh an àigh” which is translated “The blessed child.”

Lyrics: http://www.fionamackenzie.org/DuanNollaig.pdf

Video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x1EigEpZ6kU

It’s also heard in the expression “Ainm an àigh!” which means something like “For God’s sake!” (Said as an exclamation of frustration.)

Thank you so much for this article after reading it and part 2, my appreciation for the language and the complicity of it has greatly grown. It makes so much sense in what you say about it not being a direct translation as culturally it makes no sense, I never realized how different it truly was. My husband and I have decided not to get our tattoos in gaelic and rethink how we will do it. I am Irish and Scottish and he Scottish, our saying comes with great meaning within our family and us so we thought this would be a great idea, but after both reading all of this we are going a different route. I am now looking into learning the language as I am even more intrigued about it and the culture. I did email the translator you suggested as I really want to know how to say and read our saying in Gaelic just for us personally.

Thank you

Angela, thanks so much for your comment. I’m so glad to hear that you are learning the language and seriously considering the meaning as you do your tattoo research. Learning Gaelic can be so interesting and rewarding. Please feel free to post any questions or comments you may have as you go along!

I’m all in favour of preserving Gaelic but having it on police cars and ambulances in Edinburgh is just annoying people and associating it with SNP politics. This cannot be good for the language to be turned into a partisan issue.

Goodness, that escalated quickly!

The Gaelic language is not in fact a partisan issue in Scotland. The Tories were the ones who initiated the increased public support for Gaelic with the Broadcasting Act (1990). Gaelic is not a Tory, Labour, LibDem, or SNP issue. Moreover, I am in Nova Scotia, Canada, where our attempts to preserve and promote Gaelic have no relationship to U.K. party politics.

If you find the public appearance of the Gaelic language anywhere in Scotland “annoying,” or you believe that other people do, this is an indicator that you, or they, hold linguistic and ethnic prejudice against Gaelic and Gaelic speakers. This prejudice is what ails the language and our Gaelic community.

For details please see Ch. 3, “Discourses of death and denigration: Ethnolinguistic differentiation and the ideology of contempt” in my book Gaelic Language Revitalization Concepts and Challenges: Collected Essays, https://www.bradanpress.com/books/gaelic-language-revitalization/

Hi Emily! It was wonderful to read your post, since it´s very informative. My name is Hernán and I´m from Argentina (you´ll wonder why an argentinean person is asking such question… well, it´s just love!). I´m next to tatto my arm with a scottish gaelic phrase, but, at this very moment, i have a doubt: How should I say “I will always love you” properly?

– Bidh gràdh (gaol) agam ort an còmhnaidh / gu bràth / gu sìorraidh…

Ok, Tapadh leat!

I hope you can help me! (Sorry for my no good enough English…)

Hernán chòir, tapadh leibh gu mòr (thank you very much)! I’m sorry that I can’t provide Gaelic translations on this blog (as mentioned in the post above), but please check out part 2 of this post at https://gaelic.co/gaelic-tattoo-2/ for some suggestions on how to find a suitable phrase for your tattoo. Subscribe to my blog e-mail list to receive updates about my forthcoming book on the topic! (Scroll all the way down to the bottom of this post to see the black “Subscribe” box in the right corner.)

I’m so glad I came across this article. I’m reading up on Scottish Gaelic. I love researching Scottish culture since I have many ancestors that came from there. I agree that people who create bad celtic tattoos are only damaging what I think is such a beautiful language. Personally I would rather get some sort of symbol rather then words, but I don’t have any tattoos not yet at least 🙂

I’m curious to know then that if most websites don’t give the true translation in Gaelic, any idea how can I listen to Gaelic music and get the right meaning/translation? I have a lot of songs I love and I’ve seen the English translation on one site but then I go to another and it has different wording, or even the Gaelic words themselves are not right. I understand your never going to get it exactly because of the language break down but It would be nice to at least have a sense of the true meaning of a song.

Stephanie chòir,

Deagh cheist (good question) — the answer is actually a little complicated! I’d like to answer your question in a separate blog post actually. Would it be OK with you to quote your original question there?

absolutely, I would appreciate it!

Hi , my nana shortly just passed and was hoping to get her favourite song translated into Scots Gaelic , we are from Edinburgh and my nana was the only one in the family that could and would speak Gaelic to us , if you could translate it would be so great .

“Dreams can come true

Look at me babe I’m with you

You know you gotta have hope

You know you gotta be strong”

Thankyou so much

Tia 🙂

Tia, tapadh leibh gu mòr (thank you very much). I’m so sorry for the loss of your grandmother. Unfortunately I can’t provide Gaelic translations on this blog (as mentioned in the post above), but please check out part 2 of this post at https://gaelic.co/gaelic-tattoo-2/ for some suggestions on how to find a suitable phrase for your tattoo that could help you honour and remember your grandmother. The Gabrielle song lyrics you requested would actually be really difficult to translate properly into Gaelic because of the idiomatic (slang) language and the English cultural ideas in the song. Do you know whether your nana also had a favourite Gaelic song?

You can also subscribe to my blog e-mail list to receive updates about my forthcoming book on the topic of Gaelic tattoos, which might help. (Scroll all the way down to the bottom of this post to see the black “Subscribe” box in the right corner.)

Ooops. I have a tree of life and teaghlach tattoo (I got this 10+ years ago). I wanted the Gaelic term for family. How off the mark am I?

Thank you for your comment! Nach buidhe dhut (aren’t you lucky)! You are right on the mark. And here is a dictionary entry that gives an example of how to pronounce it (click on the little triangle under “Audio” to play the soundfile):

http://learngaelic.net/dictionary/index.jsp?abairt=teaghlach&slang=both&wholeword=false

Funny you left this comment.I have a tattoo I have had for 4yrs stating “riamh ar ais síos” Which i was led to believe correctly translated to “never back down” in Irish. Is it wrong!??

Daniel, I understand a bit of Irish but not enough to confirm. I’m going to ask my fellow tattoo handbook author Audrey Nickel to answer your question – she is the author of The Irish Gaelic Tattoo Handbook which is the Irish counterpart to my Scottish Gaelic Tattoo Handbook. She’ll comment below.

Hi Daniel,

I’m very sorry to have to tell you this, but your tattoo isn’t at all correct. I really wish I had better news for you, but whoever “translated” that just did a search on the English words “never,” “back, and “down,” without considering that Irish (which is what the Irish form of Gaelic is called in Ireland) might express things differently, or that the words might not make sense out of context.

“Riamh” can mean “never,” but only when it’s paired with a negative verb. An example would be “ná géill riamh” (“never yield/give up”). In other contexts it can mean “before,” or “ever.” It’s an adverb, so it really can’t stand on its own.

“Ar ais” means “back” as in “come back” (“tar ar ais”). It doesn’t mean “back” as in “back down.”

“Síos” means “down” in terms of “going down.” For example, if I’m going down the stairs, I can say “Tá mé ag dul síos an staighre.”

The other issue your translator encountered is one of idiom. We don’t use “back down” to mean “yield” or “give up” in Irish. Instead we’d use something like “géill” (“yield”) as in “Ná géill riamh” above: “Never yield.” Another way to express this idea in Irish is to say “Seas d’fhód” (“Hold/stand your ground”).

I’m really sorry to be the bearer of bad news. 🙁

This may be a ridiculous question, but is thre a difference between Scottish Gaelic and Irish Gaelic? What are the differences if they aren’t the same?

Thank you in advance

It’s not a ridiculous question at all! I actually have another blog post that helps to explain it — it’s here (see point #4, “Scottish Gaelic is similar to Irish”): https://gaelic.co/what-is-gaelic/

If you have more questions about the differences after reading the blog post, then please feel free to post another question on that post, and I’ll do my best to answer it. Tapadh leat (Thank you)!

Dear readers, I’m excited to announce that soon my new book will be published: “The Scottish Gaelic Tattoo Handbook: Authentic Words and Phrases in Scotland’s Celtic Language.” If you’d like to sign up to be notified when it’s published, please click here: http://eepurl.com/bT0ZVL

Thank you very much!

Hi! I’ve read your post about Scottish Gaelic tattoos gone wrong. I’m actually thinking of getting one. I know I might be one of those annoying people who ask for translations. But I’ve been searching the Internet for online forums and communities and found no help. I recently fell in love with the language and think it’s one of the most romantic (don’t know if many would agree) sounding languages I’ve ever heard. Please let me know if you’d be kind enough to try and translate my “to be” tattoo phrase. I’d be very happy and grateful if it’s possible. thanks!

Thank you for your comment. Unfortunately as my blog post explains, I can’t help with individual tattoo translations.

However, I’m publishing a new book in May titled The Scottish Gaelic Tattoo Handbook: Authentic Words and Phrases in the Celtic Language of Scotland.

You can sign up for the email list on this page. Mailing list members will get a discount code when it’s published:

https://gaelic.co/tattoo-book/

Le dùrachdan (with best wishes),

Emily

Hi Emily – I loved your article -and I’ve just been reading the comments here and, God love ya, you’ve the patience of a feckin’ saint!!! BTW – whats Gaelic for “Cray-Cray” -just kidding!! keep up the good work! Joanne (from Ireland)

Mìle taing Joanne 😀

“Mile taing” translates to crazy?

No, it’s “a thousand thanks”! 🙂

Tha gu dearbh!

I love this site and these comments. Keep up the good work.

I stumbled upon your delightful post accidentally, researching my family. I am descended from the Craigs, and I read the crest and saw that it was in Latin, and I wondered why. What happened to make a Scottish family write their crest in Latin, not in ScottsGaelic, which I sort of assume to have been in existence for the duration of Latin…is there a website that maps out the historical events that shaped our language, and is there a concerted effort to bring it back from the brink of extinction?

That’s a good question. There is a very good free report by Mike Kennedy titled Gaelic Nova Scotia, published by the Nova Scotia Museum, that would give the Scottish history you’re looking for (https://gaelic.novascotia.ca/sites/default/files/files/Gaelic-Report.pdf). Latin was widely used in medieval Europe, by Gaels as well as Lowland Scots and others.

There are indeed concerted efforts to bring Gaelic back in both Nova Scotia and Scotland — you can read more about them in the various other posts here on the Gaelic Revitalization blog! Have fun poking around gaelic.co and if you have any more questions, don’t hesitate to ask!

One important thing to remember is that “crests” and “coats of arms” were awarded by the English, and thus were almost always in either English or Latin. They were never a Gaelic custom.

Thank you for this! My grandfather was from Cape Breton and he and his friends would speak Gaelic (driving my Yankee grandmother crazy) and sing songs in Gaelic, and I’ve always wanted to learn. The grammar is intimidating but I’ll check out your post on where to get started.

Hello everyone!

Congratulations on your page! I feel weird asking this. I feel like an intruder. My brother has died recently and I want to make a tatoo with the phrase “my brother lives in me” in Scottish Gaelic. I think it’s something like this: “Mo bhràthair beò ann rium”. It is correct?

Thank you very very much.

I’m very sorry for the loss of your brother. Unfortunately, as mentioned above in the blog post, I can’t offer free translations on the blog. I noticed that you got a few answers from the Facebook group that you posted in. I would just say again that Google Translate is not a reliable source for tattoo translations. I have just published a new book titled The Scottish Gaelic Tattoo Handbook which is available through Amazon and other online bookstores. Subscribe to the Bradan Press email list at http://eepurl.com/b0WymH for a 10% discount code and more info on availability.

Would like to know the translation of my family crest, “Tuagha tulaig abu”, if anyone can help with this, it’s very important!!! Thank-you. Tuagha tulaig abu

Alan,

Thank you very much for your comment. As mentioned above in the blog post, I can’t do individual translations here on the blog. I have just published The Scottish Gaelic Tattoo Handbook which provides nearly 400 Gaelic words and phrases with English translations. I am working on a second book which will include family and clan mottos, last names (surnames), and first names, so I will add yours to the list. Otherwise I can recommend the translator mentioned above in the article. Best wishes and feel free to subscribe to the blog for more about Gaelic language and culture!

“Tuagha tulaig abu” the mac Suibhbne motto translates to “The People of Tulaig (The Co. Donegal region of Ireland) forever.”

I’ve always wondered if Scottish Gaelic was a mixture between Irish Gaelic and the Picts language, seeing that the Picts really did not die out just changed. History at its finest. What Scots era do you favor? Just as a personal question.

Hi Emily, great article, I am interested in learning Scots Gaelic. Im In England, do you know of any classes or reliable

Online resources I can use?

Alex, thank you for your post. If you are in London, City Lit offers courses in London (http://www.citylit.ac.uk/catalogsearch/result/?q=Scottish+Gaelic&cat=285). Outwith London, at this time it looks like an online distance course might be your best bet. Sabhal Mòr Ostaig in Skye offers a reputable distance course for beginners called “Cursa Inntrigidh”: http://www.smo.uhi.ac.uk/en/cursaichean/cursaichean-air-astar/. Apart from that, there is some old information from 1998 (old and probably out-of-date) in a quiet corner of the SMO website: http://www.smo.uhi.ac.uk/gaidhlig/clasaichean/Sasainn/. I hope you can find what you are looking for. As far as online resources, the free site http://www.learngaelic.net in Scotland is very good!

The Clan Anderson motto is Stand Sure. Can you give me the proper Scottish Gaelic translation?

Thank you for your comment! As mentioned above, I can’t do free translations on the blog. However, I am currently working on volume 2 of The Scottish Gaelic Tattoo Handbook which will contain Gaelic translations of the clan mottos! Please feel free to sign up on the Bradan Press e-mail list at http://www.bradanpress.com for more info, and to be notified when the second Gaelic tattoo handbook is published! Tapadh leibh!

I found this post interesting both as someone interested in Gaelic, (but never doing a tattoo), and as someone with a degree in Latin.

Gaelic and Latin share the tattoo problem. So many people who don’t know how Romance languages work, (which would help if not knowing Latin at least), get the bug for a tattoo. I’ve seen a girl have “flies with pigs/with wings” on her foot, and another who identified herself as a man/hero among other mistakes.

I’m also in Oklahoma and can verify that we have a good Scottish heritage community in this state.

I am interested in getting a tattoo that has the gaelic war cry (located on a plaque at St Bartholomew’s hospital). I just wanted to check this is correct: Bas Agus Buaidh (Death and Victory). thanks!

Thank you for your comment. I’m so sorry, as the blog post explains above, I can’t give individual translations for free here. I am writing a sequel to my first book, The Scottish Gaelic Tattoo Handbook, which will include the correct versions of Gaelic clan and military mottoes like the one you mention. Please join the Bradan Press email list to get advance notice when the book is going to be published! (Click on the black ad banner in the sidebar to sign up on the email list.) Le dùrachdan, Emily

“If you’re lucky, they might make an alternate suggestion which would be more suitable.”

Tsk, tsk! Alternative, not alternate. And “alternative suggestion” is verging on the redundant. So, how about: If you’re lucky, they might suggest an alternative which would be more suitable.

I’ve just ordered your bookm for work seriously on my future tatoo in scottish gaelic.

I’m passionate about Scotland and its history and I appreciate à lot “forgotten languages”…

But I have one question, is there a particular alphabet for gàidhlig ?

Thank you so much.

Sandra

Sandra,

Tapadh leibh gu mòr for ordering the book! Good news, your question about a particular alphabet is actually answered in the book! It’s in Chapter 4, “The Basics of Gaelic Writing”, which covers the Gaelic alphabet, Gaelic spelling rules, accent marks and apostrophes, suggested fonts, and pronunciation. Hope that helps.

Thank you so much for your answer !!

I look forward to receiving your book.

And I will search in the chapter 4 🙂

Again thank you from France !

Sandra

I wish I were bilingual, aside from the tattoo requests it seems wonderful to be able to express sentiments that you can’t get across with English. My grandmother spoke Irish Gaelic fluently having picked it up from her father but he was always discouraged from using it so failed to teach it thoroughly to any of her siblings. Unfortunately she died when I was a toddler so what little I had picked up was quickly forgotten and she had only taught my father basic phrases like instructions. Only my great uncle and father can remember much, and it tends to be in the form of creative swearing when drunk. It’s a huge shame, but one I’m hoping to rectify, I’m trying to wrap my head around it but as a dyslexic it was rather complicated learning English, so it’s going slow.

It’s wonderful that you’re giving it a go — learning another language can be very beneficial for many different reasons! I wonder if it might be good to focus more on listening/watching and speaking, rather than reading and writing, to increase your enjoyment. Check out the other blog posts here on Gaelic.co — I’ve written one with tips for learning the language (“Learning Scottish Gaelic”) and one about the benefits (“Too Old to Learn Gaelic?”). I hope you enjoy the learning process!

I randomly came across your site and I found it such an interesting read. As a Scot who’s spent the majority of his adult life in Japan I’ve had many giggles at the “Japanese” tattoos that some people I know have got. Either because it’s usually either Mandarin or gibberish, or because, as you explained, the cultural concept just doesn’t translate. Yes the words are literal but the meaning is lost. Although I was wondering if the Saor Alba one was meant to be Free (liberate) Scotland albeit with a “typo”. That is often used as a pro independence phrase in Scotland.

Thanks for your comment! そうですね、there are a lot of similarities between the situations. With Saor Alba, it just doesn’t sound that great as an imperative. The literal words are OK but it’s used as a pro-independence phrase in Scotland by non-Gaelic speakers. It’s not how a Gaelic speaker would phrase it. I gave some better-sounding alternatives in The Scottish Gaelic Tattoo Handbook!

Thanks for your reply and clarification. I’m not a speaker of the Gaelic and find it hard to learn alone without an understanding of pronounciation but I do love languages and speak Japanese, Scots and some Spanish so I’m always interested in these discussions. Ironically as I have a number of Irish friends most of the pronounciation I know comes from Irish Gaelic. If you could clarify one thing for me I’d appreciate it. Is Slainte in SG pronounced Slanji as most Scots would say or similar to the Slawnsha that the Irish would say? Or would this change with dialect across the Gàidhealtachd.

日本語も話しますか。

はい、日本語もできます。昔は日本に住んでいました!私の苗字はマキュワン藤田です。。。Scottish Gaelic pronunciation has almost no relationship to Scots – they are from different language families! (Celtic and Germanic, respectively.) So the pronunciation is more similar to Irish. Here is a good general pronunciation of slàinte in Scottish Gaelic, I hope this answers your question! (click on the speaker icon): http://learngaelic.net/dictionary/index.jsp?abairt=sl%C3%A0inte&slang=both&wholeword=false

Hello Emily,

How are you? I hope you don’t mind if I ask the following question about my name? (not a tattoo question btw)

My birth name is Steven, but use Stef more. I have been looking to change my name legally for years to a Gaelic spelling of Stephan/Steven which I believe are some of the following,;Stíobhan ,Steafan or Steafán.

I like the spelling of the last Steafán as it can be shortened to Stef (nickname). I believe there is a Scottish Gaelic spelling and Irish spelling with fada above the a, (á) which I presume is the Irish Gaelic way of writing the name.

I also beileve the above are masculine. Is there a varation for Stephan/Stephani both M/F ? I saw Stiana which is aparantly a very old and rare Irish way to spell Stephan/Stephani both masculine and feminine, but can’t confirm the authenticity of the information.

I am Scottish and also have Irish linage down the gene pool so both spellings are acceptable to me.

I do hope it’s not just another boring frustrating question that gets put your way. I would just really like expert advise before I start the procedure of changing my name legally for paperwork etc. As you can imagine, that would be an embarrassing predicoment on formal legal documents if I have the Incorrect info.

your assistance would be greatly appreciated.

Yours sincerely ,

Stef.

1) Dear Americans (and anyone else),

You’re not Scottish unless you are from Scotland. If your great grandwhatever immigrated to the states and you were born and raised in the US, then you should be saying you are of Scottish descent. Please learn this. It comes across as quite ignorant when you claim a nationality that (most of) you have had little or nothing to do with. It’s not correct to say you’re Scottish when you’re of Scottish descent or Scottish heritage. (And even that claim is debatable thanks to DNA.)

2) Emily- Maybe you should write a post about how people need to learn to do their own homework. Haha! “Where can I take a class on…?” “Where did this originate?” “What’s the difference between…?” etc. When I had a question as a child, I was told to look it up. If I did and clarification was needed, then ok, but adults didn’t just give me answers unless I put forth effort on my end. I know most people were raised the same. Why have we forgotten that? “Why use my own time to find the answer when I can just ask you to do it for me!” Folks, please understand how many times a day, “I’ll just ask this quick question,” happens. If it is something you could have easily found on your own, you’re just being lazy. Be more considerate of other people’s time.

3) How do you say, “I don’t do tattoo translations” in Scottish Gaelic? Asking for a friend. Hahaha!

These people ARE doing research. Asking people who know more than you do about a subject has always been a valid form of research.

When people ask similar questions on my blog, I try to help them find a place where they can get the answers they need.

Hi Emily – I am of Scottish /Irish Decent- my late father gave me a love of the sea which I wish to acknowledge through a simple phrase

Live Life …..Love the sea in Scottish Gaelic (which he spoke in very limited amounts)

I need to understand correct translation in the context of the statement, opposed to simplistic word for word translation which may have a different context in the Celtic world.

many thanks.

Scott, thank you for your message. As my blog post mentions above, I don’t do translations on this page, and unfortunately that phrase is not included in my book. That phrase sounds simple in English, but it would be quite different in Gaelic (I’d suggest that you read The Scottish Gaelic Tattoo Handbook to get a sense of why). And as you have probably already noticed, Google Translate will butcher it. I suggest to consult the professional translator who I mention at the bottom of this blog post! Dùrachdan, Emily

hello, im trying my best to stumble through these comments, it very clearly states you do not translate for tattoos, i am a tattoo artist and am asked often for tattoos in a language neither the client or myself speak, for those reading this comment please stop asking us to mark you in a language/culture you do not care to learn or take part of……..rant over.

i am currently attempting to teach myself scottish gaelic , my family came to america on a plane but my father was kind to the drink, so alas im doing it myself. i have recently purchased the 12 week book,unfortunatley without the cds, is there a system that you recommend with some audio help?

i am having trouble with naming my business i wanna name it colrblind but not sure if it is noun first, this book is hard to follow, it looks like it should be dathdhall, but could be dath hall, any light on this would be great, or just a better system than i am using to learn. i live in central washington and not a lot here for help.

clearly im no writer, thanks a ton for all the information please keep writing im loving this.

p.s. got your book at my shop for those that insist, at least itll be accurate,also how to you get the text to look accurate in your typing? slàinte….. had to copy and paste that

Thanks for your comment! I would say definitely find some audio input. I don’t know if it’s possible to find the CD that goes with the book separately. Check my blog post “Learning Scottish Gaelic” for more suggestions, and especially explore the “Free Resources” section and also the comments (in the comments, some people have said they can find “Mango” at their local public libraries, which sounds promising).

Giving your business a Gaelic name is VERY tricky for multiple reasons. It’s actually as tricky as getting a Gaelic tattoo… and there is even more money involved in naming and opening your business than in getting even a big tattoo. I would be very cautious about that choice. “Colourblind” is “dath-dhall” in Scottish Gaelic (pronounced a bit like “dah-ghowl”) but your customers would probably try to pronounce it “dath-doll” rhyming with “bath-doll”). The English mispronunciation doesn’t have a great sound to English ears and it’s positively painful to Gaelic ears. I would try to come up with at least 3 alternatives, and run them by one or more fluent speakers, as well as several local folks who have no Gaelic at all, before making a decision.

I don’t know how far you are from Seattle, but there is a longstanding Gaelic group there, Slighe nan Gàidheal. They offer great Gaelic classes and workshops. There are a number of fluent speakers and teachers, and perhaps someone there might be able to consult with you on how to name your business, maybe even barter for it. Definitely look them up and get in touch.

TAPADH LEAT GU MÒR for buying the book! There is also now an Irish Gaelic Tattoo Handbook that does the same thing for Irish — spread the word!

Speaking of the Irish tattoo book, the author has written a great blog post on how to type the accents for Irish. HOWEVER, those tend to be the opposite direction of the ones for Scottish Gaelic. Here’s a blog post about typing French which should cover most of what you need: French accents.

‘S e do bheatha ,

hope thats right……… if not , thank you very much for the information and resources, also the suggestions.

Gabh air do shocair

I’m actually half Scottish and didn’t know it until recently. I really want to get a Scottish Gaelic tattoo that says ‘I am strong’. I have Googled it and the translation said, “is mise làidir”. Is that wrong or right?

Shelby, thanks for your comment. I’m not able to do free translation work on the blog — take a look above at the blog post, and click through to read Part 2, and you’ll see suggestions for how to get the translation you want! I also offer more suggestions in The Scottish Gaelic Tattoo Handbook!

Loved this post, very informative…I visited Scotland for the fist time this summer and fell in love with the country and its people, so of course I want a Gaelic tattoo…or runic tattoo. But now I’m rethinking the whole thing, if finding a correct translation for Gaelic would prove difficult I can’t imagine about the runes, even if I paid for the translation how could I tell if it was correct?? I am actually going back to Scotland next week, I’ll do more research…in person 🙂

Hi Emily. Thanks for a very interesting post. I grew up in the Highlands and was taught Gaelic in primary school in Alness and Conon-Bridge in the late 1970’s. I thought I had forgotten all of it until I read “Tapadh leibh” and it all came back! (well, some of it).

I am currently having the apparently compulsory mid-life wobble, and am considering a tattoo. I now live in Ireland and intend to be very sure that any text is proper (Scottish) Gaelic!

I would be interested to know if in your opinion, the Picts would have been Gaelic speakers? I am aware that relatively little is know about them, apart from their carvings, but would like to have some text to go along with a Pictish image.

Thanks again for the post regardless of whether you can give any info.

Hi Emily, Dia dhuit Emily,

I thoroughly enjoyed your article and read it in it’s entirety, even the comment section. To which I must ask you the following, Can you translate a tattoo for me? I believe it’s “Pog mo thoin”! (I don’t know how to add the fadas on my computer yet) hahahah. Like someone said above, you have the patience of a Saint. God bless you for keeping your demeanor with everyone who asks you, in every round about way possible, to translate a tattoo!!!! Good grief. Good luck to you! p.s. I wonder if there’s a deep rooted reason down in the depths of my psyche why I almost failed every English class I’ve ever taken, but yet, I’m morbidly intrigued by the grammatical nuances of Gaeilge. Or maybe I’m just getting old.

Slainte!

Hello,

Judging by the previous comments I’m also one of the many that has stumbled upon this page in my noble quest for truth and knowledge.. ok, well to atleast make sure I don’t get something silly tattooed on me

You must be fed up of having to explain that you don’t do free translations etc, so how much would you charge for a simple translation? I would be happy and willing to pay x amount for peace of mind and your seal of authenticity before going under the needle

Not sure if this is something you would be interested in, but for a straightforward translation that would probably take you a few moments you could charge £5?

You could obviously charge more for a more detailed or lengthy translation

Unfortunately we all need money to get by so this could be a little earner for you, or you could donate it to charity?

Again only if you had the time or could be bothered ha

Just thought I’d ask

Neal (Niall) chòir,

Thank you for your comment. You have probably gathered from my delay in replying that the issue is not simple! 🙂 I have written a book, The Scottish Gaelic Tattoo Handbook, which offers nearly 400 translations, double and triple checked by two professional Gaelic editors. I’m happy to confirm whether particular requests are contained within the book or not. There’s an ad for the book somewhere on this page, if you click on it it will take you to Amazon.com, but the book is also available at Amazon.co.uk and through the Gaelic Books Council (where the purchase supports Gaelic book publishing in Scotland).

There are a number of reasons why I don’t run a separate bespoke translation business, one being that as well as the blog, I run my own business (a Gaelic publishing company), and have all the normal accoutrements of a life (hobbies, charity fundraising, dogs, family). So it’s not a case of “can’t be bothered” — I’ve just assessed that given my limited time, it’s not the best way for me to share my areas of knowledge about Gaelic. However I am planning a sequel project to the book, which will offer even more translations — so please subscribe to my email list to be notified when it launches!

As you’ve gathered from the above blog post, tattoo translations are almost never simple, and they can be stressful since they are often connected with strong emotions (particularly when someone has lost a loved one). I do have two colleagues who offer professional translation services — the contact info for Michael Bauer is at part 2 of this blog post: https://gaelic.co/gaelic-tattoo-2/ and the other, Alasdair MacCaluim, can be reached at https://www.fiverr.com/gaelicalasdair. Feel free to contact either one of them for your needs!

Dùrachdan,

Emily

Hi! I don’t want to get it wrong but I want my tattoo to say “Be Kind” in Gaelic. Google translate says it transfers to “Bí cineálta”. Is this correct?

Hi there! That isn’t Scottish Gaelic (Gàidhlig), it’s Irish (which is also sometimes known as Irish Gaelic or Gaeilge). (The difference between them is explained here). If it’s Irish you’re after, then please visit my fellow tattoo book author Audrey Nickel’s blog, The Geeky Gaeilgeoir – her posts will explain how to get a good Irish translation. If it’s Scottish Gaelic you’re after, your request is not in the glossary of my book, The Scottish Gaelic Tattoo Handbook, but I will add it to the list for the sequel! In the meantime, please read part 2 of this blog post for suggestions of how to get a good translation for a tattoo!

Where can I find psalm 23 in Scott’s Gaelic, Thanks

Ryan,

Psalm 23 in Scottish Gaelic — I’ll just have to retype that for you from the Gaelic Bible, today’s a bit hectic so please give me a day or two. May I ask what you are interested in doing with it? That could help tailor my answer to you.

If it’s for singing or reading aloud in church, recently found a video on my hard drive that I never posted online, where a small group of us sang the versified (metrical psalm) version for a United Church of Canada national conference in Halifax a few years ago. The old custom was to sing it to the tune “Martyrdom” and that’s how we did it. I may be able to get that up on YouTube for you soon as well. It’s not sung in a Gaelic precenting style, just straight.

Here’s a bit to tide you over, the first 2 verses done in a precenting style from Cape Breton:

https://www.mun.ca/folklore/leach/songs/CB/4-02.htm

Psalm 23 from the Gaelic Bible:

Salm XXIII

1 Is e an Tighearna mo bhuachaille: cha bhi mi ann an dìth.

2 Ann an cluainibh glasa bheir e orm luidhe [laighe] sios: làimh ri uisgeachaibh ciùin treòraichidh e mi.

3 Aisgidh e m’anam, treòraichidh e mi air slighibh na fìreantachd air sgàth ainme féin.

4 Seadh, ged shiubhail mi toimh ghleann sgàile a’ bhais, cha bhi eagal uile orm; oir tha thusa maille rium: bheir do shlat agus do lorg comhfhurtahcd dhomh.

5 Deasaichidh tu bòrd fa m’ chomhair ann an fianuis mo naimhde: dh’ung thu le ola mo cheann; tha mo chupan a’ cur thairis.

6 Gu cinnteach leanaidh maith agus tròcair mi uile làithean mo bheatha; agus còmhnuichidh mi ann an tigh an Tighearna fad mo làithean.

The metrical psalm version (in rhyming verse for singing) at the back of the [Protestant] Gaelic Bible:

1 Is e Dia féin a’s buachaill dhomh,

cha bhith mi ann an dìth.

2 Bheir e fa’near gu’n luidhinn sios

air cluainibh glas’ le sìth:

Is fòs ri taobh nan aimhnichean

thèid seachad sios gu mall,

A ta e ga mo threòrachadh,

gu min rèidh anns gach ball.

3 Tha ‘g aisig m’anam’ dhomh air ais:

‘s a treòrachadh mo cheum

Air slighibh glan’ na fìreantachd,

air sgàth ‘dheadh ainme féin.

4 Seadh fòs ged ghluaisinn eadhon trìd

ghlinn dorcha sgàil a’ bhàis,

Aon olc no urchuid a theachd orm

ni h-eagal leam ‘s ni ‘n càs;

Air son gu bheil thu leam a ghnàth,

do lorg, ‘s do bhata treun,

Tha iad a’tabhairt comhfhurtachd

is fuasglaidh dhomh a’m’ fheum.

5 Dhomh dheasaich bòrd air beul mo nàmh:

le h-oladh dh’ung mo cheann;

Cur thairis tha mo chupan fòs,

aig meud an làin a th’ann.

6 Ach leanaidh maith is tròcair rium,

an cian a bhios mi beò;

Is còmhnuicheam an àros Dé,

ri fad mo rè ‘s mo lò.

I’ll see what I can do about getting that old video up soon, if I haven’t done it in a week then send me an e-mail through the blog to remind me! “Martyrdom” was the preferred Scottish Presbyterian tune for this in the old days. (Nowadays it’s a different tune in English congregations, but I still prefer Martyrdom.)

OK here you go! Thank you for asking as you reminded me it was high time to put this video out there. It’s really not my finest singing (and I am not a fine singer to begin with) but “done” is better than “perfect” as they say. This is Rev. Ivan Gregan (minister of my church, Port Wallis United Church in Dartmouth), local Gaelic teacher Joe Murphy, and me. I’ve added the metrical Psalm words below the video. Also if you have questions about how to pronounce particular words, check in the dictionary at http://www.LearnGaelic.scot, there are pronunciation soundfiles for a lot of the words (also know that some of these words are spelled archaically and may not show up in the dictionary). Ah, Gaelic…

https://youtu.be/TdxEUCAv8pk

It would be for me to sing, and possibly say in a church someday. That’s awesome,

‘Sann à Cheap Bhreatainn a tha mi, Our people are from the Mabou area, now living in New Waterford. I’m taking a huge interest in it, would you no any teachers or classes etc…looking forward to the type out as well, Tapadh leat!

Agus: math fhéin!! Yes there are classes! Check with Comunn Gàidhlig Cheap Breatuinn in Sydney first — I think there are classes in Sydney and then they should also know what else is going on around CB. Angus MacLeod does a wonderful summer immersion every year near Englishtown, depending how flexible your schedule is, and of course the Gaelic College. There are other immersions too that are irregular. Ask the Sydney folks, they should be able to get you in touch, if not then send me an email through the blog. Sin thu fhéin, cum ort, keep going! 🙂

Thank you So so much big help!. I’ll will definitely be making some phone calls for sure. I’ll keep in touch over the year to let you no how my progress is going. The first version of psalm 23, that’s the cathloic version I take it ?? Once again Tapadh leat!

The first version is also from the (Protestant) Bible but you can certainly use it. There is a Catholic lectionary version in Scotland, but copies can’t be purchased anywhere. I don’t think it is substantially different though. There is a new Gaelic Bible translation coming some time in the next few years, which will use more updated grammar and spelling — I’m looking forward to it. If you’re going to read the psalm in worship, then maybe talk to the priest, they may even have the Gaelic version or know another priest who has it. Or they will let you know if that version is OK. Also, there’s an ecumenical Gaelic service every year in Cape Breton, in the month of May, so keep an eye out for that too. It alternates among the different churches, Catholic, Presbyterian, and United Church of Canada. Yes, let me know how you get on agus mo bheannachd ort!

Ryan, I just did a new blog post based on your question. Mìle taing for the inspiration! Here it is: https://gaelic.co/psalm-23/

Thank you for your posts, I have not considered a tattoo, but I have been interested for some time in learning Scottish Gaelic. I will be looking into places near me and reputable places online and now I have a place to start. I came across part two on Pinterest of all places! I’m Glad I did there is a lot of great information that I have found.

Wonderful! Mo bheannachd ort as you embark on your learning journey! Also take a look at this post on that: https://gaelic.co/learning-scottish-gaelic

I’m getting a tattoo and hopefully get this all spelled out correctly. A Trinity Knot with … my love, my family, my life. Any help?

Yes, I have most of those options in the glossary of my book, The Scottish Gaelic Tattoo Handbook. Interestingly, I see that Amazon currently has it on sale (as of June 6, 2018)!

What is proper Irish Gaelic for Peggy (not Margaret). I have seen both Peigi and Peghai. I already see the difficulty of writing this in Ogham because of the letter P. Eventually I want to write the name in Ogham but am at a loss for a resource.

I would also like to confirm proper Irish Gaelic for “my sister”. Is it “mo dheirfiur”?

Soul Friend: I have used more than one English to Irish translator and got “cara anam”. But I see reference to “anam cara” when I search. Is their a difference between the two? Which is (more) correct?

Peggy, all of your questions can be answered by another book that my company publishes, The Irish Gaelic Tattoo Handbook by Audrey Nickel. You may also wish to check out her blog, The Geeky Gaeilgeoir!

I can offer you a couple of freebies, Peggy, but I would like you to get them confirmed at the Irish Language Forum (www.irishlanguageforum.com), because the first rule of translation seeking is ALWAYS ALWAYS ALWAYS GET THREE FLUENT PEOPLE IN AGREEMENT BEFORE PROCEEDING WITH ANYTHING PERMANENT.

(Sorry for the shout, but it’s really, really important)

1) The Irish form used for “Peggy” is “Peigí” (“Peig” would actually be more usual, but you will hear the former as well). “Peghai” is very, very wrong. For one thing, it violates an important Irish spelling convention. For another, “gh” in the middle of a word in Irish is usually pronounced as if it were a “y” (and “gh” can never be pronounced as a hard “g”). My guess is that “Peghai” was something put together by someone who didn’t actually speak Irish, but who wanted something that looked Irish to them (these people are very fond of “gh” for some reason).

2) For “my sister,” it depends on whether you are speaking TO your sister or speaking ABOUT her. Speaking to her, you’d say “a dheirfiúr.” That’s because Irish has a special case — the vocative case — used for direct address. If you want to speak ABOUT your sister, however, it is “mo dheirfiúr.” BTW, don’t forget the accent on the “ú.” Irish words (as well as Scottish Gaelic words) are misspelled if the accent is left off (or if it’s put on where it doesn’t belong)

Oh, and just in case, we use a different word for “sister” if we’re speaking of a nun (just in case that ever comes up).

3) Both “cara anam” and “anam cara” are very, very, very, VERY wrong for “soulmate.” You’ll find a bit about that in this blog post Emily put together for St. Patrick’s Day, and even more in my book, “The Irish Gaelic Tattoo Handbook.”

https://www.boredpanda.com/erin-go-wut-real-life-irish-tattoos-that-make-us-cringe/

Hope that helps a bit! If you’re really interested in Irish, I strongly recommend you check out the Irish Language Forum I mentioned above. There are lots of lovely people there who are more than happy to help with anything to do with Irish. You have to join, but it’s free.

Hope this helps!

I came across this blog while doing research for a book I’m writing, and also on my family history. Our family name is Shaw, of the Highlands and Islands, not lowlands. I keep coming across several references to the Highland Shaws having the name derived from “sitheach” and also “sithech”, both allegedly meaning “wolf”. I’m having a hard time confirming this academically, do you have any insight? As for the book, I’m working on a character whose name I’d like to be – in Scottish Gaelic- Dark or Black Wolf. I’m a very new learner to the language, and don’t want to form any bad habits by relying on the dictionary and/or translation sites. Thank you for putting up with all the questions and for keeping the language alive! I hope to be able to do the same someday 🙂

Here is a good list of Scottish Gaelic surnames on Wikipedia, compiled from published sources: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Scottish_Gaelic_surnames. I checked with an academic friend who says it is her understanding that the name Shaw was a Lowland name and the Gaelic “translation” or version was added later. If you want to use elements of Gaelic in your fiction and are not a Gaelic speaker, the best thing would be to consult a professional translator, who can also talk to you about whether the choices are appropriate in cultural terms. For that I can recommend my friends Alasdair MacCaluim (https://www.fiverr.com/gaelicalasdair) and Michael Bauer (akerbeltz.com). Best wishes on your book!

I am looking for the correct translation of Do Not Fear to use as a tattoo

Hi there, as mentioned in the post above I don’t do individual tattoo translations, but if you click on Part Two of the post (the link is at the bottom of this post), there are links to one or two custom translation services at the bottom of the post. My book, The Scottish Gaelic Tattoo Handbook, does not have this exact phrase but there are some similar ones in it: http://www.bradanpress.com/gaelic-tattoo-handbook Tapadh leibh and I hope this helps!

Hey! 🙂

I saw a tattoo which spelled “dhagaigh” on a person. The person told me that it would mean “home” in scottish gaelic.

As a beginner gaelic learner myself I only know the term “aig an taigh” for the meaning “home”. It would be interesting for me what the difference about these words is. Would be grateful if you could tell me! 🙂

Simona

Simona,

Thank you for your comment! “Taigh” means “house” whereas “dachaigh” means “home” – “my home” is “mo dhachaigh” and “going home” is “a’ dol dhachaigh.” To make it even more fun, another Gaelic expression for “at home” is “aig baile” (even though “baile” usually means “village” or “town” in other contexts). I hope that makes sense! “Dachaigh” and its related expressions are very useful for Gaelic learners!

Thank you very much for your detailed explanation. It really helped me!

Tapadh leibh! 🙂

‘Se ur beatha!

Hi Emily! I’m trying to get the correct pronunciation of “God King”. From all the research I’ve found Dia Righ but that’s literally just God and King so it doesn’t seem that would be correct but could be wrong. Any help would be appreciated. Thank you!

Dose this work as a tattoo,

Alba Shaor (top row)

Flag than

(bottom row,, No ?mark lol)

Beatha?

As mentioned in the post above, unfortunately I don’t provide free tattoo translations. But in my book, The Scottish Gaelic Tattoo Handbook, I do recommend the top one, “Alba Shaor”. As I also recommend in the book, you have to be very cautious about how you combine words and phrases and I wouldn’t combine those two that way. For more feedback about why, and what would work better instead, in the sequel to this blog post, I give contact info for two professional translators with very reasonable rates, who can advise you on custom combinations and translations!

I would like to know how it is written in scottish gaelic “I don’t forget you” and also “my love” .

I’m not a native english speaker but I would like to have a correct writen tattoo in honour of my child who is buried in Glasgow.

Thank you, gracias.

i am doing a memorable on my back for the family members that have passed away. i have a lot pf scpttish in my family and we are really big on the culture. however i cannot get the correct translation of what i want to put on my back it reads-

Just because you are not here, you will never be forgotten.

One day, we will be together again. But till then, you will forever be remembered in our hearts and souls.

can you help me with the correct translation?????

I’m amazed at the number of people here asking for translation help. Did youse not read the bloody post?!

Thank you so much for an interesting bit of education! I stumbled upon this while looking for “something Gaelic” to honour my Scottish heritage (not necessarily a tattoo). What REALLY struck me was your explanation of the fragility of the language, due largely to attempts by past governments to stamp it out. I live in Canada where we have a long history of Residential Schools attempting (and mostly succeeding) in destroying Aboriginal languages. These languages are about culture and identity – not party tricks for the rest of us. Although I am still passionate about my Scottish roots, I have decided that I will not diminish that heritage by using elements of a language I’m not fluent in. I would LOVE to learn the language – and will someday! But I will take it seriously and respect it .

Goodness, the tattoo requests never stop. Your patience is exemplary.

I followed a link to your book on Amazon, where it lists with an option to “Add to Baby Wishlist”. Obviously this is a wishlist for people holding baby showers & christenings where there will be gifts (hooray for consumerism), but my initial thought was “are people really tattooing their infants?” Silly, but I thought a smile among all the requests might be nice.

Very good book, too 🙂

Tapadh leibh / Thank you! Obh obh, clearly I need to write a proper Gaelic baby name book soon! I wouldn’t recommend anything in the Tattoo Handbook glossary as a name for a person! (Although some could work as inscriptions for baby gifts like photo frames!) 😀

hi, i need this translated into gaelic for a tattoo but i can never trust the internet. “you are enough” is what i need translated pls help!

Hi Macy, thank you for visiting the Gaelic.co blog! Please read the post above for the explanation of why I don’t do Gaelic tattoo translations here. And check out the link to part 2, which you’ll see at the bottom of the post, to find out how to get the translation you want!

I’m getting a tattoo that’s very close to heart and I want it to read correctly. I want the translation for (Brothers above All) and I’ve seen what Google says it is. What is the correct Scottish way of saying this?

I know it’s not Scottish Gaelic but does “fir na dli” translate to men of law? I already have the tattoo.

I presume it’s Irish? I’m sorry, it wouldn’t be right for me to be confirming an Irish language phrase when I don’t speak Irish. However, you can check with the author of The Irish Gaelic Tattoo Handbook, Audrey Nickel, The Geeky Gaeilgeoir! Her blog is at https://thegeekygaeilgeoir.wordpress.com/.

Hi Scott,

Unfortunately, your translation has a couple of issues. One is easily fixable, but the other could be problematic.

The first issue is that there needs to be a right-slanting (acute) accent over the “i” in “dli” — in other words, it should be “dlí.” Without the accent it’s misspelled. That’s something I’m sure your tattoo artist can fix relatively easily.

The bigger issue is the word “na.” Because “dlí” is grammatically masculine, it should be “an.” I don’t know much about the actual art of tattooing, so I don’t now how difficult that may be to correct.

With the corrections, yes…it means “men of law” or “men of the law.”

Just to add: Unless you mean male humans specifically, the more usual term would be “lucht an dlí.”

My Mother can understand Scots Gaelic when she hears it but has lost the ability to speak it because of lack of people to speak it with.